Amazon’s push-button-ordering gizmo could be a harbinger of things to come on the Internet of Things. But is it a hacker’s dream?

Lee Teschler – Executive Editor

lteschler@wtwhmedia.com

On Twitter @DW—LeeTeschler

The online retailer Amazon wants you to order items like laundry detergent or coffee by pushing one of its Dash Buttons. A Dash Button is a Wi-Fi connected device that reorders a specific product with the press of a button. When you’re running low, simply press Dash Button to place an order with Amazon.

Users setup and manage Dash Buttons through an app on a smartphone. When everything is good to go, the Button can send a notification to your smartphone every time an order is placed, letting you cancel an order before it ships if need be.

There’s also a version of the Dash Button that can be programmed to do other things: place an Amazon order for something else or execute non-ordering tasks such as control smart appliances such as lights. But this programmable Dash Button costs about $20 rather than the $5 that buys a Dash Button already dedicated to a specific product. The hardware on the two is identical. So there is a sizeable web community devoted to analyzing the cheaper version with repurposing in mind.

One problem with the Dash Button, as with other appliances making up the internet of things, is that they open up the possibility of being hijacked by hackers with nefarious intent. Cyber security experts say the usual reason criminals hack IoT devices is to use them as proxies that hide the hacker’s true location online. Hackers do this to mask cybercriminal activity such as frequenting underground forums or engaging in credit card fraud.

But there’s another potential security problem with the Dash Button: It contains a microphone. The mic is used to configure the Dash Button through ultrasound when the smart phone running the Dash app uses iOS. (Android phones use Wi-Fi for configuration.) Those who’ve analyzed the configuration sequence say the ultrasound signals take the form of ASK transmissions in the 18 kHz range. Problem is, a microphone able to pick up ultrasound will also pick up near-by conversations. Thus theoretically, the Dash can be turned into a surreptitious listening device.

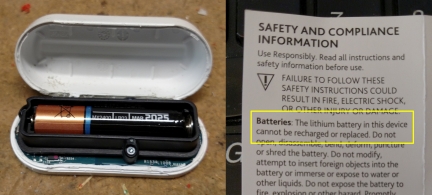

Perhaps the main factor that mitigates the Dash Button’s security problems is its battery. The battery is neither rechargeable nor replaceable. Amazon says a Dash Button should be good for about 1,000 button pushes before its battery dies.

The upside of this relatively short life is that a Dash Button won’t last long as a rogue proxy server or as a listening device. Those who have analyzed Dash Button circuitry say it draws 200 to 300 mA when on, 2.3 μA when in sleep mode. Thus the Dash Button will last awhile when it only draws hundreds of milliamps during brief button pushes. But if operated as a proxy server or listening device, it would draw this kind of current nearly all the time. From the AAA cell’s current versus service hour curves, the Dash Button might last just four hours if run in active mode this way.

To add a bit of confusion, there is another Amazon product resembling the Dash Button but called, simply, the Dash. It is a device for adding items to orders on AmazonFresh, a grocery deliver service. An analysis of the Dash device, published on the web, found that the Dash carried basically the same circuit as the Dash Button but with a barcode scanner and a replaceable battery. Thanks to the onboard microphone, the Dash can also accept voice commands.

Inside an ordering button

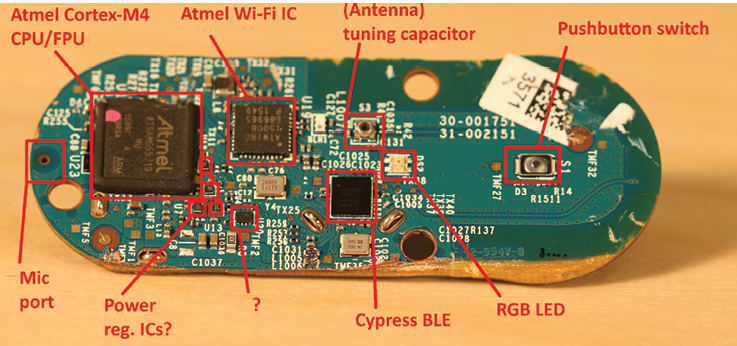

The Dash Button hardware has gone through a couple of revisions that have involved changing the main processor, battery, microphone, and Wi-Fi chip. Earlier versions carried an STM32F205 microcontroller and a Broadcom BCM43362 Wi-Fi module. The microphone was from InvenSense and the tab-welded lithium-ion battery was an Energizer.

The more-recent version we examined contained quite different hardware. The processor is now an ARM-based unit from Atmel (ATSAMG55J19A). The Wi-Fi chip is from Atmel as well (ATwinc1500B). Also onboard is a Bluetooth Low Energy chip from Cypress Semiconductor (CYBL10563-68FNXI) and a flash memory chip from Micron (N25Q032) that is about the double the size (32 Mbit) of that on the earlier versions. Bluetooth is the means by which the Dash Button communicates with an Android phone during setup.

One noteworthy item is the battery. The earlier version’s lithium-ion Energizer cell has been swapped for a Duracell AAA unit that sits in a battery holder. (The lithium-ion cell was tab-welded to the PCB.) The AAA cell is less expensive and holds less energy than the lithium battery it replaces, 1.15 A-hr compared to about 1.3 A-hr.

The reason for the battery change seems to be that Dash designers found a way to reduce the amount of energy consumed during a click. According to an analysis by physicist Matthew Petroff, the new Dash Button’s energy use is about 4.3 ± 2.2 J per activation while the original Button used 16.4 ± 0.1 J per activation.

There are several small ICs on the PCB that lack enough markings to be identified. Commenters on other Dash Button teardowns have speculated that four of them residing on the top surface of the PCB make up some kind of power regulation network. But in that the board carries a boost regulator power supply chip, it is hard to imagine what purpose additional power regulator chips might fulfill.

Also of note is the antenna network. The Dash Button contains a tuning capacitor that is evidently part of a matching network for the Bluetooth and Wi-Fi antenna. The antenna itself is printed on the PCB near the edge at one end. We found only one antenna, implying that both the Bluetooth and Wi-Fi radios share it.

Overall, the Dash Button can be viewed as a possible prototype for what much of the IoT could end up looking like. Hobbyists are already figuring out ways of recording data every time a Dash Button is pushed and using that information to control household appliances. At $5 each, if Dash Buttons are a vision of the internet-connected future, the IoT will be relatively cheap.

References

• Matthew Petroff’s Dash Button teardown

• Reverse Engineering the Amazon Dash Button’s Wireless Audio Configuration

• Main Processor: Atmel SAMG55

• Bluetooth: Cypress CYBL10563-68FNXI

• Boost converter: Texas Instruments TPS61200

• How I Hacked Amazon’s $5 WiFi Button to track Baby Data

My first button (as a light switch) worked for a month then died — all it does now is flash the red light. So when I set up a second button I put a counter on it. It died at 194 presses, which allowing for half a dozen during setup persuades me that someone clever at Amazon has programmed it to die after 200 presses with no order acknowledgement. Even at the Black Friday price of £1.99 that’s 1p per operation, too expensive.

Anyone know what packet to send it to persuade it that an order has been placed ?